Scholarly Article Effect of Family Characteristics on Voting Participation

Agreement why citizens choose to vote in elections is ane of the most studied questions in political scientific discipline. While a myriad of individual- and institutional-level factors are known to be related to voting throughout one's life, scholars of political behavior have pinpointed boyhood and early on adulthood as a formative catamenia of political evolution (Dinas Reference Dinas2013; Schuman and Scott Reference Schuman and Scott1989). In detail, a child'south family unit environment has been shown to influence their long-term political appointment (Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson Reference Cesarini, Johannesson and Oskarsson2014; Gidengil, Wass and Valaste Reference Gidengil, Wass and Valaste2016; Gimpel, Lay and Schuknecht Reference Gimpel, Lay and Schuknecht2003; Pacheco Reference Pacheco2008; Plutzer Reference Plutzer2002; Verba, Schlozman and Burns Reference Verba, Schlozman, Burns and Zuckerman2005).

Family is an of import source of political socialization; children learn about politics from, and detect the political behavior of, their parents. Exposure to political discussion in the dwelling has been consistently demonstrated to exist one of the strongest predictors of whether or not a child volition vote equally an adult (Gimpel, Lay and Schuknecht Reference Gimpel, Lay and Schuknecht2003; Pacheco Reference Pacheco2008; Verba, Schlozman and Burns Reference Verba, Schlozman, Burns and Zuckerman2005). In improver to teaching children about politics, parents also provide non-political resource that assistance to foster a child's after political appointment. While scholars of political behavior have firmly established the importance of the family unit in shaping adult political participation, this research has non taken into account that growing upwardly in a specific family can be a different experience for children of different birth orders. In this article, we examination whether the club in which a child is born into a family influences their likelihood of voting as an adult. There are at least three prevailing theories linking birth order to adult outcomes.

The starting time two focus on how nascency order affects the cerebral development procedure. The confluence theory, based on the work of Zajonc and Markus (Reference Zajonc and Markus1975), maintains that earlier-born siblings are advantaged because the average family intellectual environment declines with each successive nascency as children are less intellectually developed than adults. That is, whereas commencement-borns exclusively receive intellectual stimulation from their parents during their initial years of life, later-borns must besides interact with their older siblings, which hampers their evolution relative to kickoff-borns. The resource dilution theory formulated by Blake (Reference Blake1981) makes a similar prediction about the human relationship between nascence social club and cognitive development, but stresses the admission to household resources. As the size of the family unit grows, the share of parental attention and resources each later kid receives is smaller since it must be distributed amidst all children.Footnote ane In support of this resource machinery, Blackness, Grönqvist and Öckert (Reference Black, Grönqvist and Öckert2018) constitute that parents spent less time discussing school work with later-built-in children.

A third theory, posited by Sulloway (Reference Sulloway1996), focuses instead on interactions between siblings and argues that children sort themselves into distinct 'family niches' in order to successfully compete with one another for parental resources. Commencement-borns develop traits, such as conscientiousness, that allow them to preserve their dominant status in the sibling hierarchy, whereas younger siblings effort to differentiate themselves from their siblings past existence unconventional and more sociable. Blackness, Grönqvist and Öckert (Reference Black, Grönqvist and Öckert2018) provide empirical evidence that birth order is correlated with different personality traits and that first-born children are more likely to choose occupations requiring leadership ability and conscientiousness.

To the extent that birth order is related to cerebral development and personality, information technology could too be expected to bear on political participation. There is potent and compelling evidence that both cerebral ability (Dawes et al. Reference Dawes2014) and diverse personality traits such as the Big V factors (Gerber et al. Reference Gerber2011; Mondak et al. Reference Mondak2010) constitute of import determinants of political activeness. Yet while a handful of descriptive studies have investigated whether starting time-borns are overly represented amidst elected officials (Andeweg and Berg Reference Andeweg and Berg2003; Forbes Reference Forbes1971; Hudson Reference Hudson1990; Newman and Taylor Reference Newman and Taylor1994; Somit, Arwine and Peterson Reference Somit, Arwine and Peterson1994; Zweigenhaft Reference Zweigenhaft1975), the importance of birth gild has been of greater interest to economists, sociologists and psychologists than to political scientists. The dearth of enquiry on political outcomes is probable due to the blazon of data necessary to cleanly divide the influence of nascency order from confounding factors like family size and birth cohort. Recent work on birth order in other domains has utilized large population registries containing information on family structure, allowing researchers to examine within-family differences in adult outcomes to convincingly place the effect of nativity lodge (for example Blackness, Devereux and Salvanes Reference Black, Devereux and Salvanes2005).

We utilise population-wide data from Sweden and Kingdom of norway to study the importance of nascency social club for voter turnout. Our within-family estimates evidence that the probability of voting is monotonically and strongly decreasing in nascence society. The results also suggest that the birth-order differential is greater the lower the boilerplate turnout rate. Nosotros show that these results are externally valid by investigating the link between nativity society and turnout in a number of samples from four other, non-Nordic countries. Finally, we shed low-cal on possible mechanisms by showing that nativity club relates to attitudinal factors known to predict voter turnout. We also show that socio-economic status accounts for office of the birth order influence on political participation.

Institutional Setting and Data

To study the human relationship between birth order and voter turnout, we utilise administrative data on validated turnout from four recent elections in Norway and Sweden. In Kingdom of norway, nosotros study the national parliamentary election in 2013 and the local-level elections in 2015, and in Sweden, the European Parliamentary election in 2009 as well as the ballot to the national parliament in 2010.

In Norway, the turnout data have been obtained from electronic voter records for all municipalities that had computerized their systems. The number of Norwegian municipalities using electronic records is increasing over time. Consequently, our data cover 28 per cent of all eligible voters in 2013 and 43 per cent in the 2015 election.Footnote 2

Since electronic voting records are not used in Sweden, the turnout data accept instead been gathered by scanning and digitizing the complete election rolls for the 2009 and 2010 elections. For these two elections, we have access to validated individual-level turnout data for 95 per cent of the electorate and the reliability of the digitized data has been shown to exist very high (Lindgren, Oskarsson and Persson Reference Lindgren, Oskarsson and Persson2019).

For both the Swedish and Norwegian samples, the turnout information are merged with various administrative registers using unique personal identifiers. The linked datasets comprise detailed data on family relations, including nascence order, as well as various demographic and socio-economical characteristics (see the Appendix for a more detailed description of the data and the institutional context).

Nosotros accept invoked a number of sample restrictions in order to ensure consistency across countries, elections and model specifications. Most importantly, nosotros restrict our analyses to individuals who accept at least one and at most 4 siblings.Footnote 3 Moreover, the samples are restricted to families in which all siblings are aged xx–65 at the time of the elections. To reduce measurement error in the nativity-social club variable, we further restrict the samples to native-born children of two native-born parents and exclude individuals who have grown upwards in families with twins. With these restrictions, the sizes of the samples used for the empirical analyses range from near 300,000 (Kingdom of norway 2013) to 2,580,000 individuals (Sweden 2010).

Empirical Interpretation

Effigy 1 shows that voter turnout is markedly lower amongst individuals of higher birth lodge in each of the four elections studied. The force of the relationship appears to exist inversely related to the overall turnout charge per unit. For the election with the highest turnout (Sweden 2010), first-built-in siblings have a 6-percentage-point higher vote propensity than that of 5th-born siblings, whereas the respective figure for the election with the everyman turnout (Sweden 2009) is almost twice every bit large (11.5 percentage points).

Figure 1. Turnout by nativity order

Information technology would, however, be a error to interpret these raw correlations causally considering the human relationship between nativity club and turnout is likely to be confounded by a number of factors that vary across and within families. I such gene is family size, since it is but larger families that accept children of higher birth social club (Blackness, Devereux and Salvanes Reference Black, Devereux and Salvanes2005). Moreover, children of higher nativity society belong to more contempo cohorts than their older siblings and therefore the relationship betwixt birth order and turnout may also be confounded by age or secular trends in turnout. Similarly, higher-gild children accept older parents, which may as well bias the birth-guild estimates if not adjusted for (Black, Grönqvist and Öckert Reference Black, Grönqvist and Öckert2018).

To handle these challenges, we rely on a within-family regression model of the following blazon:

(1)  $$y_{ij} = \alpha + \sum\limits_{chiliad = 2}^m {\beta _kI} ( {BO_{ij} = k} ) + {\Gamma }^{\prime}{\rm X}_{ij} + \mu _j + \varepsilon _{ij, }$$

$$y_{ij} = \alpha + \sum\limits_{chiliad = 2}^m {\beta _kI} ( {BO_{ij} = k} ) + {\Gamma }^{\prime}{\rm X}_{ij} + \mu _j + \varepsilon _{ij, }$$

where yij denotes the issue of interest (voting) for individual i in family unit j, BOij records the birth society of the individual, μ j represents family unit-level (mother) fixed effects, and ɛ ij is an individual-level error term. The stock-still effects account for the importance of all family characteristics shared past siblings – including, but not restricted to, sibship size, parental age and socio-economic status – and thereby assure that there are no confounding across-family processes at work. Even with the within-family pattern it will, however, be necessary to control for potential confounders that vary between siblings. For this reason, nosotros also include the vector Γ′X ij in the equation with controls for nascence cohort and gender.

Results

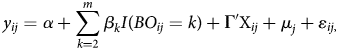

We present the results from the inside-family regression models in Table 1. Since nosotros will compare coefficients across models, samples and groups, we employ linear probability models instead of nonlinear models (Mood Reference Mood2010). However, as the results in Appendix Table A3 prove, the overall pattern of effects is similar if nosotros use a conditional logit model instead.

Table 1. Birth order and turnout, baseline results

There is clear evidence of a monotonically increasing negative effect of nascence social club on voter turnout in all four elections. The estimates besides support the view that the magnitude of this human relationship grows stronger as overall turnout declines. In the two national elections, where voter turnout is above eighty per cent, the differences in vote propensity between first- and second-borns are 1.8 percentage points (Norway) and i.2 per centum points (Sweden) and betwixt beginning- and fifth-borns 5.1 and 3.3 percentage points (run into Columns i and 4 of Tabular array 1). For the Swedish election for the European Parliament in 2009, where overall turnout was below 50 per cent, the corresponding differences are as high as 4.4 and x.3 percentage points, respectively (Column three). The turnout differential with respect to birth order for the Norwegian local ballot, where turnout was about 66 per cent, falls in betwixt the lowest and second-highest turnout election estimates (Column 2).

The magnitude of these turnout differentials is large. For case, the expected difference in turnout between a get-go- and fifth-born sibling in the Swedish European Parliament election was almost one-fourth of the average turnout in that election. To further put the magnitude of these associations into perspective, Appendix Table A1 reports within-family estimates of one of the strongest predictors of voter turnout highlighted in the literature: having completed a college degree. The differences in turnout rates between first- and fifth-borns amount to virtually two-thirds of the corresponding college differences.

Our main findings are robust to changes in model specification and sample restrictions. In particular, nosotros show in the Appendix that the results are similar for men and women (Tabular array A2) too as when not including whatever restrictions on the individual'south age (Table A4). As afterward-born children are more probable to grow up with divorced parents, nosotros find it reassuring that the results are similar when we restrict the samples to individuals from stable families (Table A5). While somewhat less precise in the sample with the fewest observations, nosotros also notice that the design of estimates seems to be similar in families of unlike sizes (Tables A6 and A7).

Finally, we test for heterogeneity across historic period differences between siblings (Table A8) and parental education (Table A9). We find some, although not very stiff, evidence that the clan between birth order and voter turnout is somewhat more pronounced among siblings who are close in age (at to the lowest degree in Sweden) and in less-educated families. These differences are rather small and imprecisely estimated and should therefore not exist overstated.

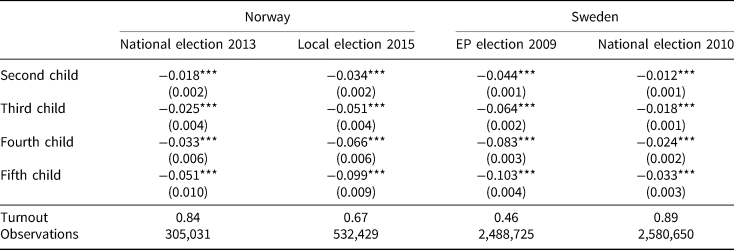

Our analysis reveals that birth society has a strong and robust issue on voter turnout in both Norway and Sweden, and that the magnitude of these voting differentials seems to be inversely related to overall turnout. 2 natural follow-upward questions concern external validity and possible mechanisms underlying the link between birth order and voter turnout. In Appendix Table A10, nosotros present results from v samples across four countries (Deutschland, Switzerland, the United kingdom and the U.s.) that all include information on birth order and voter turnout. Table A10 also displays estimates based on pooling the five survey samples. Although the estimates from each of the not-Nordic samples are all insignificant, the kickoff-borns in the pooled sample are significantly more likely to vote than their siblings. The overall pattern of the estimates in these smaller samples corroborates the findings in the two Nordic countries.

The main results from these analyses are summarized in Effigy 2. The effigy displays betoken estimates from within-family models, regressing turnout on a dummy indicating first-born status (as opposed to later-borns) from all samples.Footnote 4 Solid squares denote significance at the five per cent level. Two patterns stand out in the effigy. Outset, in all samples the showtime-built-in turnout premium is positive. Secondly, the magnitude of the turnout divergence between starting time- and after-borns decreases as the overall turnout charge per unit increases.

Figure two. Showtime-born turnout premium in nine samples (within-family estimates)

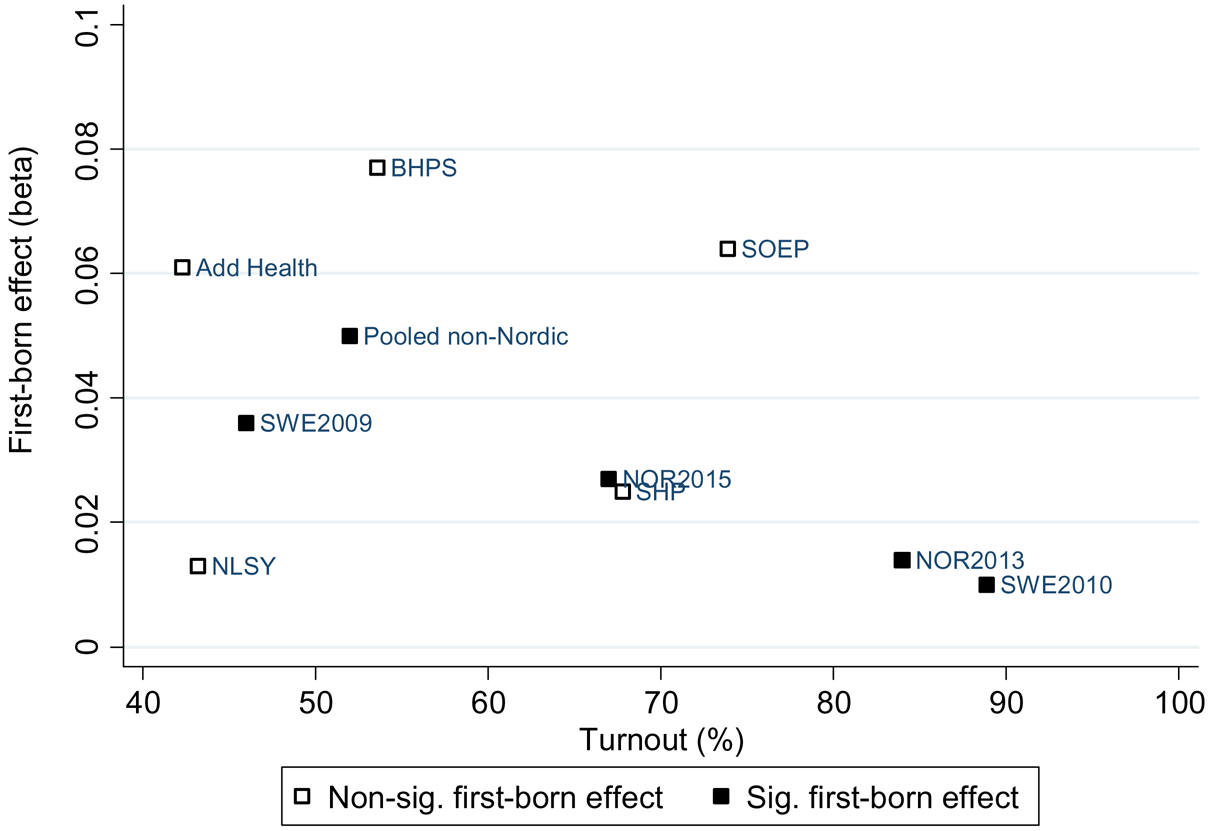

Turning adjacent to potential mechanisms, in Figure 3 we examine the extent to which the socio-economic position accounts for the observed relationship between nativity lodge and turnout. The lite greyness confined in the figure show the unmediated turnout effects reported above, and the night gray bars indicate the corresponding estimates when controlling for (percentile ranked) didactics and earnings. Absolutely, mediation analyses are complicated, and we do not control for all the variables that are correlated with the mediators and turnout. Thus the conditional coefficients should not be given a causal interpretation (for example, Imai et al. Reference Imai2011). Nevertheless, the regression results point that there are birth-society mechanisms affecting voter turnout that are orthogonal to those influencing earnings and instruction as there are still sizable turnout differentials with respect to nascency lodge. To judge from these results, better education and earnings outcomes of earlier-born siblings can, at almost, account for between one-3rd and 1-one-half of the overall turnout upshot. As can be seen from the error bars, which correspond 95 per cent confidence intervals, the reduction in the birth-guild coefficients when controlling for socio-economic condition is usually statistically significant. The conviction intervals exercise not overlap except for some of the higher-club effects in the Norwegian sample, which contains fewer observations.

Figure 3. Conditional birth-gild effects

Another possibility is that role of the influence of birth order is mediated by unlike attitudinal factors shown to predict voter turnout in earlier studies. Appendix Table A10 provides some evidence along these lines based on the five smaller samples. Once once more, the estimates are somewhat imprecise but they consistently show that existence first-built-in is positively related to involvement in politics (Verba, Schlozman and Brady Reference Verba, Schlozman and Brady1995), internal as well as external political efficacy (Finkel Reference Finkel1985), and support for the norm of voting as a civic duty (Blais and Immature Reference Blais and Young1999).

Final Remarks

We exam whether the exogenously adamant club in which children are born into a family is related to whether they vote as adults. To assuredly place the effect of nascency order, we utilize population registers from two like Scandinavian countries, Sweden and Norway, that permit us to provide precise estimates from within-family models.

Across 4 divide elections, we consistently find a negative relationship between birth order and voting. Moreover, the fact that the (absolute) size of the coefficients are monotonically increasing in birth social club shows that there is more to this relationship than a elementary difference between beginning-borns and younger siblings. Interestingly, in line with Tingsten's (Reference Tingsten1937) 'police force of dispersion', the nascency-society differentials in turnout are larger in low-turnout, second-order elections. Since these elections are mostly considered by voters, parties and the media to be less important than first-order elections (Reif and Schmitt Reference Reif and Schmitt1980), they tend to have place in a more information-poor surroundings, thus making it more challenging for voters to participate. Every bit is the instance with didactics (Lefevere and Van Aelst Reference Lefevere and Van Aelst2014), factors related to birth social club announced to enable individuals to overcome the challenges of 2d-society elections.

Our investigation of birth social club and voting is based on theories that point to the differential access to resources resulting from when a child is built-in into a family. While we provide evidence that the relationship between nascence order and turnout is partly mediated past socio-economical position likewise as attitudinal predispositions, futurity enquiry should more comprehensively explore other possible mechanisms.

Substantively, the relationship nosotros find between nativity order and voting is important for iii master reasons. First, our findings suggest a more nuanced motion-picture show of how parents influence the political participation of their children. Nosotros show that siblings with the same parents develop different voting behaviors. Afterward-born children, even in a loftier socio-economic-status home, are less likely to vote than their older siblings. Therefore, measures such equally parental socio-economic status provide an incomplete picture of access to resources that are important for political evolution. Secondly, our study demonstrates how non-political factors outside of one's control, like when they were built-in (Meredith Reference Meredith2009), are of import predictors of an individual's likelihood of voting. Finally, participation differences are especially important if siblings take dissimilar policy preferences. Sulloway (Reference Sulloway1996) argued that get-go-borns are more politically conservative than after-borns, simply Freese, Powell and Steelman (Reference Freese, Powell and Steelman1999) failed to find any evidence of this based on the General Social Survey. Notwithstanding, since birth order has been shown to influence outcomes such as health (Black, Devereux and Salvanes Reference Black, Devereux and Salvanes2016), and educational (Barclay, Hällsten and Myrskylä Reference Barclay, Hällsten and Myrskylä2017) and occupational status (Black, Grönqvist and Öckert Reference Black, Grönqvist and Öckert2018), siblings may accept different preferences for specific policies. One important artery for future research is thus to investigate whether or not this is the example. Another is to examine whether the pattern found here also generalizes to other forms of political participation. In particular, it would exist interesting to use the methodology employed here to examine whether younger siblings are in fact more likely, as the family-niche theory suggests, to partake in more not-conventional forms of political participation such as boycotting or public protesting. Although the between-family study of Førland, Korsvik and Christophersen (Reference Førland, Korsvik and Christophersen2012) did non find this to exist the case, information technology remains an open question whether these results hold if we compare siblings growing upwardly in the same families.

Source: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/british-journal-of-political-science/article/birth-order-and-voter-turnout/4994D85C18E3D8BC329877265A2C935E

0 Response to "Scholarly Article Effect of Family Characteristics on Voting Participation"

Publicar un comentario